The following article is offered by Green Comma as a discussion resource for use in grades 9–12 classrooms as well as in freshmen college classrooms. The principal writer is KP Dawes, a writer and editor living in Chicago, IL. KP has worked in the education and publishing fields for almost twenty years, five of which were spent as an instructor of a course entitled “Food History and Culture.” His sci-fi young adult novel, KOPPER, is available for purchase on Amazon.

READ NOW

Amit Shah, managing director, Green Comma, suggests that classroom instructors preview the post, the embedded links, and, at least, the summaries of the books suggested at the end of the post prior to suggesting the reading to students.

This perspective on the history of civilization does mention topics that are not ordinarily discussed in high school or junior college classrooms.

All opinions are solely that of the author.

____________________________

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Attribution-NonCommercial

CC BY-NC

This license lets others remix, tweak, and build upon your work non-commercially, and although their new works must also acknowledge you and be non-commercial, they don’t have to license their derivative works on the same terms.

_______________________________________________________________

The history of food, specifically large-scale cultivation, is the history of civilization. You simply can’t have one without the other. Food has shaped us, and transformed us, and everything we have ever done or will ever do is defined by its abundance or scarcity. Our religions, governments, and every advance is built on the human relationship to food, its production, and its consumption. And we’ve always been obsessed by it. The first celebrity chef was Roman, Marcus Gavius Apicius, whose cookbooks were the rage during the reign of Tiberius. The first and most important deities were always those of the harvest, whose holidays we celebrate even to this day. And every conflict, every revolution, and war between tribes or nations, has had food, directly or indirectly, at its center.

Modern human beings first came onto the scene some 130,000–150,000 years ago. For the vast majority of that time, over 120,000 years, humans were hunters and gatherers. Thomas Hobbes, history’s most famous curmudgeon, once referred to the life of hunter-gatherers as “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short.” Yes, certainly, life spans were short, times were often difficult, and there was nary a bar of soap to be seen, but it’s now well established that hunter-gatherers enjoyed far more free time than those of us in more “advanced,” industrial societies.

This is not to say life was easier. There was violence, ignorance, and near constant danger. This was a time when there were a lot more animals on the planet and few of them friendly. It was also a lonelier existence. For better or worse there were fewer people on the planet, less than half a billion on average, and at one point as few as perhaps one thousand on the entire Earth.Because hunter-gatherers lived off what was available they had to follow migrating herds and the change in seasons meaning they were nomadic. They were constantly on the move, spending only as little as two weeks in any one place. For this reason, people never built anything permanent. No houses. No towns. No cities. But they had religion. They worshipped the Earth and the gods of nature, specifically gods tied to food and fertility. They buried their dead. And they produced art. Hunter-gatherers were not “civilized,” but they lived in complex communities, with complex cultures, and had built for themselves a niche within Earth’s brutal ecosystem.

Then, 12,000 years ago, everything changed.

At the end of the last ice age groups of people in various places around the globe stopped hunting-gathering and switched to subsistence farming. This is called the Neolithic Revolution. The invention of agriculture. It was the single most momentous event in the history of the human species and we largely don’t know why it happened.

There are theories. The weather got too dry. The weather got too wet. People got too lazy. People got too fat. People begot too many people and there wasn’t enough wooly mammoth steak to go around. Some archaeologists say farming was just too good to resist. That it was an evolutionary inevitability. At least one group thinks that a comet hit the Earthkilling off most of our food supply, thus forcing people to the plow. But increasingly, many scholars agree that intoxicating spirits like beer and wine, helped spur the switch into agriculture, if it was not the main reason for its development. In other words, as soon as people figured out how to mass produce alcohol they built civilization to make as much of it as they could drink. This is why the ancients began to keep bees and why among the first crops ever planted were wheat, barley, and grapes.

Whatever the reason for the Neolithic Revolution, the practice of large-scale cultivation changed history on Earth forever. It permanently altered the relationship human beings had not only with the soil but with each other.

Planting a seed in the ground means having to stay with that seed. It means nurturing it. Feeding it. It means becoming sedentary. It means protecting that seed from insects, animals, and especially from other people, which means raising armies, building walls, building permanent settlements. And what may begin with a tribe of warriors patrolling a few farm plots in the midst of the jungle soon develops into armies guarding the borders of vast nation-states.

Seeds transformed mud brick villages into towns, then into cities, then into countries, and eventually empires. Armies grew bigger. Wars got bloodier. Sticks and stones became spears and swords. Spears and swords became bows and guns. Guns became the atomic bomb.History is an arms race. It’s an arms race devoted to protecting that seed in the ground and by extension making sure that your people have the means necessary to survive. That your people prosper. That your people dominate. Everything we’ve built and everything we’ve created from the mind-boggling period of the Renaissance to Pokemon® Go is about that seed in the ground. All of our cities and art, engineering and science. Every single war we’ve ever fought. All the achievements and conflicts that are the sum of human history are about only this one thing. We dress it up. We add meaning, symbolism and ceremony, but at the most basic level everything is about the food we grow. About ensuring that our offspring flourish.

In the 1930s when Hitler spoke of invading the East he spoke of “Lebensraum.” Constantly, throughout his twelve-year reign, throughout the entirety of the war. It became a principal spoke of Nazi ideology. Lebensraum! Lebensraum! Lebensraum! Put simply it meant “living space,” land that could be used to cultivate food and grow the German race. The Japanese Empire had their own version of lebensraum. As did the Soviets. As did Alexander the Great. And the Mongols. And the legions of Rome.

Oppression, injustice, and daylight savings time may all be worthy of uprising, but most revolution is born out of hunger. Hungry people are desperate people. Desperate people do desperate things. They do violent things.

They destroy nations. Rome fell when it could no longer feed the mobs. The French Revolutiononly happened because Paris had no bread. Lenin would’ve been hard-pressed to find supporters for his workers’ paradise if the Russian people hadn’t been hungryfor the better part of a decade. Venezuela is about to experience much the same and for the same reasons.

Farming, removed from the modern era of pesticides, weed killers, and machinery is hard, backbreaking work. Men and women, children, tilling and seeding the land with their bare hands and stone tools. With agriculture nutrition plummets, and with it the average life expectancy. Whereas hunter-gatherers worked about four hours a day, farmers worked from sunrise to sunset. Too much rain and your crops die. Too little rain and your crops die. Insects. Disease. Fire. Farming is uncertainty. Farming is stress.

Farming under even slightly wrong conditions can lead to utter and total destruction. The Anasazi fell to crops failure, as did the Maya, and the Khmer.

But farming also means surplus and with surplus comes a population explosion and the good life for a few at the expense of the many. Specialists such as artists developed in time, trading their abstract work for money which could be traded for food. And with increased stocks of food came trade and later writing, to keep track of it all. With agriculture also came domestication of animals, social stratification, wealth, property and with-it slavery. Because there’s only one thing better than paying people for their labor: not paying people for their labor. And with slavery and money eventually came prostitution and sexual captivity. Sex became a commodity, and with it exploitation, gender inequality, and marriage, wherein one man’s daughter was sold to be another’s wife. This is why agricultural societies lean toward patriarchy while hunter-gatherers span the spectrum of social organization.

The first cities had populations in the thousands. The primary building materials were plaster and mud. The average height of residents was about five feet and mortality rates were high, both a result of poor nutrition. The average lifespan topped off in the twenties. Settlements were subject to attacks. Natural disasters. Disease. Most people, as was the custom, were the property of those in charge. Those in charge began as the biggest and the strongest. In time these glorified warlords acquired luxury, titles and eventually a perceived divine right to rule.

On the whole life was pretty bleak, and humans searched for answers. Complex religion soon developed and with it entertainment. Theater began in Athens as religious ceremony to the god of wine. In fact the most important gods were those dedicated to food and drink. The first farmers immediately started brewing alcohol en masse. And as time slogged on alcohol was refined and became increasingly more potent. To be drunk meant to commune with the gods, and so alcohol became subject to class restriction by way of price and religion. Mead and wine were reserved for the wealthy, beer for everyone else.

With agriculture also came the dog. Historical consensus is that some wolves domesticated themselves as they became reliant on human garbage as a food supply, a byproduct our early farming ancestors produced in ever larger quantities. Man and his best friend were together at last. From there selective breeding for various traits resulted in hundreds of different breeds of dog and over 400 million individual dogs living in the world today.

And as the dog was useful as a companion, protector, hunter, and general worker, the eating of dog meat became taboo. In some cultures the dog even took on divine, sometimes anthropomorphic attributes. Some worshiped the dog as a god. Bau the Sumerian god of fertility was a dog, as was Xolotl the Aztec god of fire, as was Anubis the Egyptian god of the dead. The same happened with the cat and with the horse. Useful animals became friends and companions, useless animals became steak.

Meanwhile animals too costly or difficult to effectively rear in specific environments became prohibited. This is why Jews and Muslims in Middle Eastern arid environments, for instance, were forbidden by God himself to eat pork. Feast or fast, religions of all sorts soon became the primary arbiters of diet. In some instances, such as Christianity, certain types of food became sacred while the denial of food became a form of worship.

In order for human beings to pass along their genetic data they need to be healthy. In order to be healthy, human beings need abundant food. With the development of nations, political and religious ideologies, and technologies, human beings have for the better part of 12,000 years, consciously or not, selected for their best means of survival and genetic success. Viewed in this light, capitalism or communism, religious fundamentalism or atheism, even nationality, are not choices born out of moralism or some other abstraction, but rather a form of cultural adaptation, driven solely by concerns over food security. In other words, food is not something we simply consume, it is the primary factor by which we adopt identity.

We like to believe that we have agency, or control. We like to believe that events are largely under our control. But the truth is that much of what we believe and hold sacred, much of what we value, civilization itself, is determined by a basic drive to survive and produce fertile offspring. Food isn’t an add-on, or an afterthought, it shapes us, transforms us, and defines who we are as groups and individuals. We differentiate nationalities by their cuisine. We commemorate milestones with dinners. We celebrate, annually, the spring and winter planting and harvesting seasons, though now we call them by their Judeo-Christian-Islamic names. And when our imagined communities fail to protect and nurture the seeds we’ve planted we either starve or take on new national identities, as millions of Irish did following the potato famine, as millions of Syrians do today in the face of ongoing civil war.

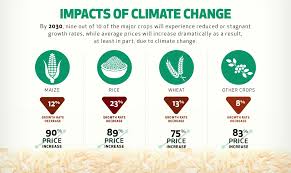

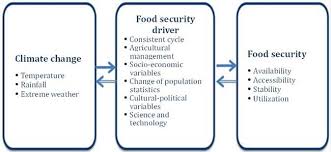

And so it is only by understanding the role of food in our history, by studying its impact on events and the shaping of cultures, can we come closer to an understanding of what it is to be human. To understand where we’ve been. Perhaps even, in the light of climate change, to understand where we’re heading next.

FURTHER READING

Collingham, Lizzie. The Taste of Empire: How Britain’s Quest for Food Shaped the Modern World. Basic Books, 2017.

Koeppel, Dan. Banana: The Fate of the Fruit That Changed the World. Hudson Street Press, 2007.

Kurlansky, Mark. Salt: A World History. Penguin, 2003.

Toussaint-Samat, Maguelonne. A History of Food. Wiley-Blackwell, 2008.

Turner, Jack. Spice: The History of a Temptation. Vintage, 2005.

READ NOW

Amit Shah, managing director, Green Comma, suggests that classroom instructors preview the post, the embedded links, and, at least, the summaries of the books suggested at the end of the post prior to suggesting the reading to students.

This perspective on the history of civilization does mention topics that are not ordinarily discussed in high school or junior college classrooms.

All opinions are solely that of the author.

____________________________

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Attribution-NonCommercial

CC BY-NC

This license lets others remix, tweak, and build upon your work non-commercially, and although their new works must also acknowledge you and be non-commercial, they don’t have to license their derivative works on the same terms.

_______________________________________________________________

The history of food, specifically large-scale cultivation, is the history of civilization. You simply can’t have one without the other. Food has shaped us, and transformed us, and everything we have ever done or will ever do is defined by its abundance or scarcity. Our religions, governments, and every advance is built on the human relationship to food, its production, and its consumption. And we’ve always been obsessed by it. The first celebrity chef was Roman, Marcus Gavius Apicius, whose cookbooks were the rage during the reign of Tiberius. The first and most important deities were always those of the harvest, whose holidays we celebrate even to this day. And every conflict, every revolution, and war between tribes or nations, has had food, directly or indirectly, at its center.

Modern human beings first came onto the scene some 130,000–150,000 years ago. For the vast majority of that time, over 120,000 years, humans were hunters and gatherers. Thomas Hobbes, history’s most famous curmudgeon, once referred to the life of hunter-gatherers as “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short.” Yes, certainly, life spans were short, times were often difficult, and there was nary a bar of soap to be seen, but it’s now well established that hunter-gatherers enjoyed far more free time than those of us in more “advanced,” industrial societies.

This is not to say life was easier. There was violence, ignorance, and near constant danger. This was a time when there were a lot more animals on the planet and few of them friendly. It was also a lonelier existence. For better or worse there were fewer people on the planet, less than half a billion on average, and at one point as few as perhaps one thousand on the entire Earth.Because hunter-gatherers lived off what was available they had to follow migrating herds and the change in seasons meaning they were nomadic. They were constantly on the move, spending only as little as two weeks in any one place. For this reason, people never built anything permanent. No houses. No towns. No cities. But they had religion. They worshipped the Earth and the gods of nature, specifically gods tied to food and fertility. They buried their dead. And they produced art. Hunter-gatherers were not “civilized,” but they lived in complex communities, with complex cultures, and had built for themselves a niche within Earth’s brutal ecosystem.

Then, 12,000 years ago, everything changed.

At the end of the last ice age groups of people in various places around the globe stopped hunting-gathering and switched to subsistence farming. This is called the Neolithic Revolution. The invention of agriculture. It was the single most momentous event in the history of the human species and we largely don’t know why it happened.

There are theories. The weather got too dry. The weather got too wet. People got too lazy. People got too fat. People begot too many people and there wasn’t enough wooly mammoth steak to go around. Some archaeologists say farming was just too good to resist. That it was an evolutionary inevitability. At least one group thinks that a comet hit the Earthkilling off most of our food supply, thus forcing people to the plow. But increasingly, many scholars agree that intoxicating spirits like beer and wine, helped spur the switch into agriculture, if it was not the main reason for its development. In other words, as soon as people figured out how to mass produce alcohol they built civilization to make as much of it as they could drink. This is why the ancients began to keep bees and why among the first crops ever planted were wheat, barley, and grapes.

Whatever the reason for the Neolithic Revolution, the practice of large-scale cultivation changed history on Earth forever. It permanently altered the relationship human beings had not only with the soil but with each other.

Planting a seed in the ground means having to stay with that seed. It means nurturing it. Feeding it. It means becoming sedentary. It means protecting that seed from insects, animals, and especially from other people, which means raising armies, building walls, building permanent settlements. And what may begin with a tribe of warriors patrolling a few farm plots in the midst of the jungle soon develops into armies guarding the borders of vast nation-states.

Seeds transformed mud brick villages into towns, then into cities, then into countries, and eventually empires. Armies grew bigger. Wars got bloodier. Sticks and stones became spears and swords. Spears and swords became bows and guns. Guns became the atomic bomb.History is an arms race. It’s an arms race devoted to protecting that seed in the ground and by extension making sure that your people have the means necessary to survive. That your people prosper. That your people dominate. Everything we’ve built and everything we’ve created from the mind-boggling period of the Renaissance to Pokemon® Go is about that seed in the ground. All of our cities and art, engineering and science. Every single war we’ve ever fought. All the achievements and conflicts that are the sum of human history are about only this one thing. We dress it up. We add meaning, symbolism and ceremony, but at the most basic level everything is about the food we grow. About ensuring that our offspring flourish.

In the 1930s when Hitler spoke of invading the East he spoke of “Lebensraum.” Constantly, throughout his twelve-year reign, throughout the entirety of the war. It became a principal spoke of Nazi ideology. Lebensraum! Lebensraum! Lebensraum! Put simply it meant “living space,” land that could be used to cultivate food and grow the German race. The Japanese Empire had their own version of lebensraum. As did the Soviets. As did Alexander the Great. And the Mongols. And the legions of Rome.

Oppression, injustice, and daylight savings time may all be worthy of uprising, but most revolution is born out of hunger. Hungry people are desperate people. Desperate people do desperate things. They do violent things.

They destroy nations. Rome fell when it could no longer feed the mobs. The French Revolutiononly happened because Paris had no bread. Lenin would’ve been hard-pressed to find supporters for his workers’ paradise if the Russian people hadn’t been hungryfor the better part of a decade. Venezuela is about to experience much the same and for the same reasons.

Farming, removed from the modern era of pesticides, weed killers, and machinery is hard, backbreaking work. Men and women, children, tilling and seeding the land with their bare hands and stone tools. With agriculture nutrition plummets, and with it the average life expectancy. Whereas hunter-gatherers worked about four hours a day, farmers worked from sunrise to sunset. Too much rain and your crops die. Too little rain and your crops die. Insects. Disease. Fire. Farming is uncertainty. Farming is stress.

Farming under even slightly wrong conditions can lead to utter and total destruction. The Anasazi fell to crops failure, as did the Maya, and the Khmer.

But farming also means surplus and with surplus comes a population explosion and the good life for a few at the expense of the many. Specialists such as artists developed in time, trading their abstract work for money which could be traded for food. And with increased stocks of food came trade and later writing, to keep track of it all. With agriculture also came domestication of animals, social stratification, wealth, property and with-it slavery. Because there’s only one thing better than paying people for their labor: not paying people for their labor. And with slavery and money eventually came prostitution and sexual captivity. Sex became a commodity, and with it exploitation, gender inequality, and marriage, wherein one man’s daughter was sold to be another’s wife. This is why agricultural societies lean toward patriarchy while hunter-gatherers span the spectrum of social organization.

The first cities had populations in the thousands. The primary building materials were plaster and mud. The average height of residents was about five feet and mortality rates were high, both a result of poor nutrition. The average lifespan topped off in the twenties. Settlements were subject to attacks. Natural disasters. Disease. Most people, as was the custom, were the property of those in charge. Those in charge began as the biggest and the strongest. In time these glorified warlords acquired luxury, titles and eventually a perceived divine right to rule.

On the whole life was pretty bleak, and humans searched for answers. Complex religion soon developed and with it entertainment. Theater began in Athens as religious ceremony to the god of wine. In fact the most important gods were those dedicated to food and drink. The first farmers immediately started brewing alcohol en masse. And as time slogged on alcohol was refined and became increasingly more potent. To be drunk meant to commune with the gods, and so alcohol became subject to class restriction by way of price and religion. Mead and wine were reserved for the wealthy, beer for everyone else.

With agriculture also came the dog. Historical consensus is that some wolves domesticated themselves as they became reliant on human garbage as a food supply, a byproduct our early farming ancestors produced in ever larger quantities. Man and his best friend were together at last. From there selective breeding for various traits resulted in hundreds of different breeds of dog and over 400 million individual dogs living in the world today.

And as the dog was useful as a companion, protector, hunter, and general worker, the eating of dog meat became taboo. In some cultures the dog even took on divine, sometimes anthropomorphic attributes. Some worshiped the dog as a god. Bau the Sumerian god of fertility was a dog, as was Xolotl the Aztec god of fire, as was Anubis the Egyptian god of the dead. The same happened with the cat and with the horse. Useful animals became friends and companions, useless animals became steak.

Meanwhile animals too costly or difficult to effectively rear in specific environments became prohibited. This is why Jews and Muslims in Middle Eastern arid environments, for instance, were forbidden by God himself to eat pork. Feast or fast, religions of all sorts soon became the primary arbiters of diet. In some instances, such as Christianity, certain types of food became sacred while the denial of food became a form of worship.

In order for human beings to pass along their genetic data they need to be healthy. In order to be healthy, human beings need abundant food. With the development of nations, political and religious ideologies, and technologies, human beings have for the better part of 12,000 years, consciously or not, selected for their best means of survival and genetic success. Viewed in this light, capitalism or communism, religious fundamentalism or atheism, even nationality, are not choices born out of moralism or some other abstraction, but rather a form of cultural adaptation, driven solely by concerns over food security. In other words, food is not something we simply consume, it is the primary factor by which we adopt identity.

We like to believe that we have agency, or control. We like to believe that events are largely under our control. But the truth is that much of what we believe and hold sacred, much of what we value, civilization itself, is determined by a basic drive to survive and produce fertile offspring. Food isn’t an add-on, or an afterthought, it shapes us, transforms us, and defines who we are as groups and individuals. We differentiate nationalities by their cuisine. We commemorate milestones with dinners. We celebrate, annually, the spring and winter planting and harvesting seasons, though now we call them by their Judeo-Christian-Islamic names. And when our imagined communities fail to protect and nurture the seeds we’ve planted we either starve or take on new national identities, as millions of Irish did following the potato famine, as millions of Syrians do today in the face of ongoing civil war.

And so it is only by understanding the role of food in our history, by studying its impact on events and the shaping of cultures, can we come closer to an understanding of what it is to be human. To understand where we’ve been. Perhaps even, in the light of climate change, to understand where we’re heading next.

FURTHER READING

Collingham, Lizzie. The Taste of Empire: How Britain’s Quest for Food Shaped the Modern World. Basic Books, 2017.

Koeppel, Dan. Banana: The Fate of the Fruit That Changed the World. Hudson Street Press, 2007.

Kurlansky, Mark. Salt: A World History. Penguin, 2003.

Toussaint-Samat, Maguelonne. A History of Food. Wiley-Blackwell, 2008.

Turner, Jack. Spice: The History of a Temptation. Vintage, 2005.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed